|

|

|

|

Virtual Communities as a Crossroads for Global Knowledge

By Marco Padula, Amanda Reggiori, and Cristina Ghiselli

Preservation. Storage. Circulation. The new frontiers of the digital

age? In all probability, yes.

The Corpus Africanisticum–Comunità virtuale per la cultura africana

in Italia, developed and maintained by the Institute for Multimedia

Information Technologies of the National Research Council is an

experimental prototype that demonstrates the process of the globalization

and universalization of knowledge that the synergy of new technologies,

communication, and specific disciplines can activate, exploiting

the interdisciplinary nature and the potentials for interconnectivity

and interaction peculiar to the Internet. By community we mean

a social group whose founding characteristic is communion: participation

by a number of members with the same objectives, sentiments, ideals,

intentions, and interests—whether of the living or with the past

through the bonds of memory. There are communities of people and

of things: a community of human beings is a collectivity cohesive

in participation; a community of things is a collection of objects,

sets of containers, and instruments for registering and organizing

documents and historical traces together with those not produced

by the same community of beings, of which they form the memory

[De Kerckhove, 1995].

An Internet site is an infrastructure supporting a virtual community

and the communication among the various communities of cyberspace.

The interaction that the new instruments like the Net both facilitate

and demand can stimulate the creativity of internauts and funnel

their participation into the production of collaborative energies.

With this prospect we can confront the theme of the redistribution

of knowledge, of the importance of sharing in it, and of how it

is the cornerstone of community life, cultural continuity, and

renewal [Lévy, 1994, 1995, 1997]. Collectivities as promotors

of significant relationships can eliminate the contradictions

between the South and North of the world and avoid the formation

of new areas of exclusion [Padula et al., 1998; Jensen, 1997,

1998].

It is interconnectivity that determines the establishment of the

infosociety, which has no territorial boundaries, is transnational,

is represented by a species that becomes community, is planetary

and global, and requires—as elements of positive growth through

the Net—ntegration and responsibility. The communicating community,

globalized in rethought time and space, makes flow its way of

life, but that flow would not exist without human participation

in the flow itself, as well as a link with reality.

Introduction of the new information technologies and electronic

media and, above all, of the Internet, has modified the relationship

between man and machine. The machine is no longer simply a computing

tool; it has become a means facilitating contacts between people—even

people of diverse cultures and countries. In this realm, interaction

no longer takes place exclusively between man and machine but

between one man and another, mediated by the machine: it has become

interactivity. The new volumes of the storage of data, of the

transfer of information, and of communication form what is almost

a symbiosis between man and machine as a kind of prosthesis—computer

supported rather than directed—and create a new system that is

not merely the digital representation of reality but that becomes

the possibility of creating virtual communities on the Net.

Searching for documentation, communicating, and interacting with

people are among the most community oriented of our daily activities.

Working communities that have agreed to live in the infosociety

extend beyond any corporate boundaries, calling for an extension

of our present concept of computer-supported cooporative work

to computer-supported community work, as suggested by Doug Schuler

[Schuler, 1994, 1998].

The increasing of digital archives is of primary importance for

the construction of a space in which the traces of the experience

that every member of the community brings to the group can be

collected. Moreover, the possibility of saving the comments and

discussion of the participants in a virtual community alleviates

the transitoriness of the contributions, making time for updating,

spreading, sharing, and developing the information available.

There is an urgent need for tools for thematic searches and for

the integration of data memorized in heterogeneous and distributed

archives. The data structures, transfer protocols, and complex

systems on which their management is based are currently the subject

of advanced studies. The role of technologists and designers is

to create a link in continuous tension between speculation and

pragmatism: while considering social needs, they are also introducing

the most abstract of ideas into the operating laboratory to conceive

solutions based on available and experimentable infrastructures,

methodologies, and languages. In this way, the virtual community

shortens the gap between technological innovation, its transfer,

and the employ of its products, so that we can expect environments

such as the social and technological—which are today divided—to

become asymptotically convergent.

The immaterial trace of the physical object is what will remain

as testimony that can be repeated in an infinite number of copies

an infinite number of times. It will even be possible to increase

and renew it—without losing its initial state and progressions—and

always maintaining a clear view of its path through life, verifiable

at every stage. And if preservation is a constant in the current

debate of technological disciplines as well as of classical disciplines,

then the storing of information will benefit equally from information

technologies. The archives' physical location, which has always

been a part of man's material culture, has no impact today on

the retrieval of the object: it is only the physical custodian

of the thing, but it can be visited—not only in reality but also

through a process of formalization and cataloguing that makes

the search easier. Consequently, electronic media also facilitate

a new dissemination of knowledge—one that is extensive, horizontal,

and intercultural.

In the virtual community, individual identity and features are

no longer inportant. Nor are professional profiles or affiliations:

only the documents circulated, the actions undertaken, and their

effects are. A virtual community is deterritorialized: detached

from physical and geographic space but dependent upon the possibility

of connecting with the Net, which permits or denies inclusion

in the virtual community. Since the invention of digital systems,

we speak of real time, in which an instant is a gesture followed

immediately by a reaction. Solar time no longer exists; instead,

we have potential immediacy: the interval is measured in the time

it takes the person addressed to answer and in the speed of the

instruments involved. Time in virtual space is measured in acts

of communication.

The virtual community is responsible for the evolution of the

document, which now resembles a channel of communication more

than it does an artifact. It becomes the concrete realization

of a semantic emergence—without a predefined description of the

contents; its singularity disappears and its outline is not precisely

indicated, unless by the URL (uniform resource locator), or Net

address, of its heterogeneous components: there is no longer a

beginning and predefined end to the reading. As a consequence

of its transitoriness, what matters in a document is the management

in time of its successive versions, the references to its dynamic

components, and the access to important information. The material

being of the object becomes a secondary aspect: the object can

be seen in a completely artificial situtation [Padula and Musella,

1997]. Virtual communities of things allow the artifical world

built by physical man—libraries, museums, and so on—that is the

human archives, to be even more artificial, since the material

given of the relationship with the object is of no import, the

object being simulated in the digital mode, allowing physical

man in his search in the virtual world easy access to the resources

of knowledge, much more swiftly, and without having to move from

his workstation. He decides what, how, and, above all, when to

access the enormous quantity of information available on the Net.

He can preserve forever, in digital form, whatever he retrieves,

and perhaps these new archives will be what, in fact, is transmitted

as memory.

On the Net, real communities are transformed into virtual communities

of navigators, whose existence depends on their interactive activity.

The virtual community of navigators—of all of those searching

for knowledge on the Net—is an effective support for the real

community, coping with problems that cannot be dealt with in reality

but that can be solved when relocated in the virtual world.

A virtual community on the Net requires two primary elements/sources

in order to exist. On one hand are the individuals who make up

the community and measure themselves against each other within

it: the community of people, composed of collectivities animated

in the active and participative, communicative, interactive mode.

Interactivity is, in fact, the characteristic that makes it possible

to communicate and take part in the construction of a renewed

space of knowledge, to which each member is called to make a personal

contribution. The interactivity that the new instruments like

the Net both facilitate and demand can stimulate the creativity

of the internauts and direct their participation toward the production

of collaborative energies. On the other hand, there must be a

reservoir of materials from which to draw the knowledge that in

the real world is contained in museums, libraries, collections,

and documents: the community of things. Virtual communities of

things represent archives, which are continuously consulted, updated,

and expanded by the members of the community, taking advantage

of the possibilities the new information and digital technologies

provide. These communities shall be the immaterial archives of

human memory [Reggiori, 1996].

The communities of persons organize the virtual communities of

things that constitute the archives of man's memory and that represent

the first step in the building of a collective memory, in that

they make it possible to reach the object of interest no matter

where it is located and no matter where the user is connected.

Virtual communities of things also make it possible to organize

surroundings for an object—that is, discussion, analysis, an exchange

of ideas, or a subjective activity—through the expansion of the

archives, or through corrections, or through variations when errors

or imprecisions have been discovered.

Interconnectivity and navigation allow members of a virtual community

to move in the space of the Ne—in cyberspace—and to access, through

simulation, the virtual community of objects, the archives, patrimony,

and information base of the virtual communities of persons.

The skeleton of a virtual community

The infrastructure of a virtual community is an Internet site,

developed through programming applications and languages that

are public—that is, ones that available at no charge on the Net.

This infrastructure provides for preservation, and it proposes—when

it does not demand—dissemination through use.

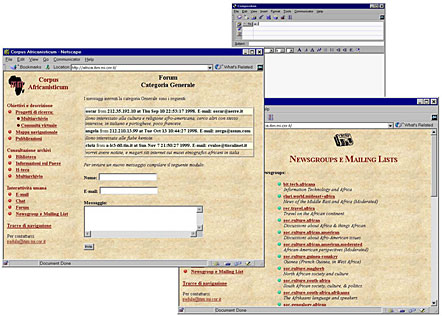

The Corpus Africanisticum–Comunità virtuale per la cultura africana

in Italia (http://africa.itim.mi.cnr.it, figure 1), addressing

for the moment Italian-speaking users, was created to exploit

the technological potentials for the preservation, storing, and

circulation—planetary and global—of African culture as documented

in Italy, as a documentary support for research in African culture

through multimedia documents in archives that can be consulted

directly in Internet, and with the intention of creating a relational

space for immigrants in Italy. The activity of the historian,

in fact, relies on extensive research through museums, libraries,

and archives located in general in different cities and countries

[Mozzati and Padula, 1996]. The Corpus is a global/virtual library

from which information can be drawn, thereby eliminating the problem

of the geographic distances separating the different archives

that form it and the persons accessing it—and making it possible

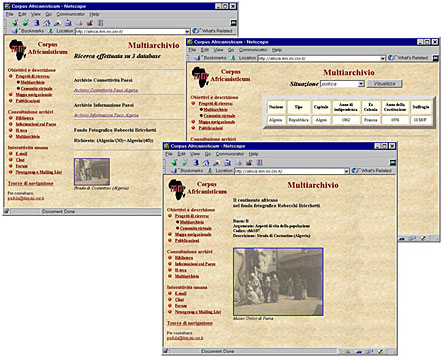

to bring together heterogeneous data (texts, images, numbers)

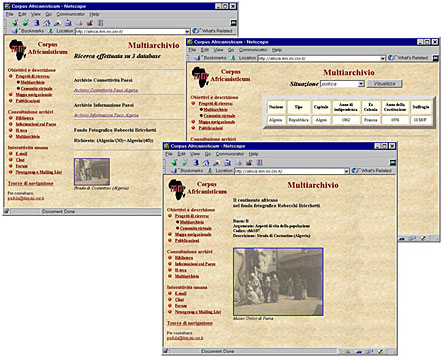

in a single document (figure 2).

Figure 1. The home page of the Corpus Africanisticum - Comunità

virtuale per la cultura africana in Italia (Virtual Community

about the African Culture in Italy)

Organization of the immaterial archives of human memory

Preservation, sustained by instruments for online storage, permits

the retrieval of documents through access to the archives from

remote stations, free of the bonds of the physical place of material

filing, and supporting the activity of the researcher.

As initially designed, the Corpus Africanisticum was simply a

virtual community of things bearing on the theme of African culture

in Italy—a reprocessing in the virtual context of the classic

concept of the library and applying the new information technologies.

This aspect has been maintained and introduced into a corrected

idea of the virtual community and continues to be an instrument

for studies and research adopting the new technologies. The initial

objectives of the Corpus included virtual elimination of the geographic

distance of heterogeneous and distributed archives and the reorganization,

through digital coding, in a single informative object—the multimedia

document—of all of the media and communication languages (text,

images, sound, and, when pertinent, video). This object was assigned

the characteristics of the hypertext: shaping it in a nonsequential

but network structure, composed of a complex of information units

(nodes) and connections (links). An intricate information organization,

transmitted in this manner, has transformed the Corpus into a

complex of hypermedia—that is, multimedia hypertexts connected

on the Net.

The Corpus, as a community of things, takes the form of a thematic

multiarchive: a collection of heterogeneous and distributed archives

grouped by subject and equipped with a structure for accessing

it that facilitates the search—by subject—for information. Its

design was inspired by the theory of MultiDataBase Systems [Pitoura

et al., 1995]: systems for the creation of an environment for

the integration of and concurrent access to multiple, distributed,

and heterogeneous databases and supplying a concise but global

view of all of the archives—a view that is not limited by the

technical choices made during its realization. The various archives

are integrated through several levels of synthesis relating the

schemata of the different archives to each other. Each schema

describes the structure of the archive by the type of data contained,

how these are related, and the operations that can be performed.

Every archive has its contents and a local schema that can be

consulted autonomously through programs that vary depending upon

its structure and the interests of the user. To integrate the

data of local archives, the local schemata must be concisely combined

in a common model (CDM, or common data model) of representation.

The mechanisms currently in use for searching in document archives

by keywords or values require the sequential access and querying

of archives, which is time-consuming and gives results that are

difficult to visualize. Progressively transforming the local schema

into a sequence of overlapping schemata through the use of a CDM

presumes the construction of an ontology—that is, a detailed description

of a conceptualization designed for reuse in different domains

of interest or data structures. The term conceptualization means

a set of concepts, relations, objects, and constraints defining

a semantic model of a domain of interest.

Constructing the Corpus also meant constructing an ontology, recognizing

the recurrent elements among the data at the global level, and

identifying the links between the various elements of information—components

of the heterogeneous documents. This made it possible to recatalog

the contents of local archives by subject and to assign the semantic

attributes that provide significant representation of the various

pieces of information.

The process produced a structure combining the semantic attributes

in a unified view of the different archives that allowed the search

for documents composed of heterogeneous elements. The definition

of this structure is an operational use of the CDM. The same archive

may belong to more than one domain of interest defined on the

basis of suited sets of concepts belonging to theontology. The

reference to the domain is particularly useful during the querying

of archives because queries addressed to the thematic multiarchives

can be translated into terms accessing the local archives involved,

thereby optimizing information retrieval.

From the technical point of view, this process requires the construction

of a complex data structure that maps the external user’s view

onto the local schemata of the various archives when they are

connected with the multiarchives. The subject cataloging of new

archives precedes their inclusion in the multiarchives. A tool

has been designed for the automatic creation—depending on the

cataloguing—of the semantic links among the new archives proposed

and those already included in the multiarchives.

The user is not aware of consulting heterogeneous and distributed

archives, because the formulation of the query and the results

obtained are as homogeneous as possible. The user may want to

select only part of the archives available. If just one archive

is selected, the concepts represented by the local schema of the

archive are visualized. If there is no common domain, the program

asks that the query be specified by value for a generic comparison.

In this way, queries are divided and translated into the syntax

of the individual querying programs of the archives. The result

is visualized as a single object (figure 2).

Figure 2. An example of the result of a query to the Corpus

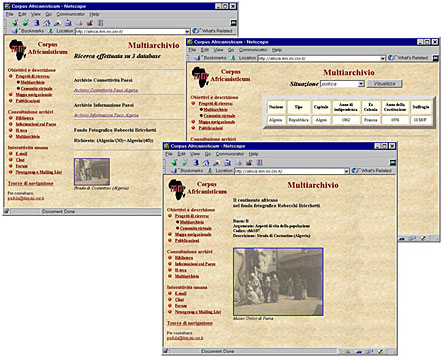

The heterogeneous, distributed archives created via different

applications can be accessed in the Corpus through an organization

by sections (figure 3).

Figure 3. Access to the virtual community of objects

The Library (Biblioteca) includes archives generated with specific

systems of information retrieval for the organization and retrieval

of texts. Textual archives can be expanded with images and hypertextual

connections among documents.

Information on the Country (Informazioni sul paese) accesses a

relational database containing, for example, information on social,

geographic, and economic conditions in African countries and on

the possibility of Internet connections.

The H-teca is composed of archives of documents in HTML (hypertext

markup language) concerning the African continent. It is a rough

mapping of the resources on the Internet that are dedicated to

Africa. The data have been partially cataloged, stored, and organized

through information retrieval programs developed for their retrieval

by direct querying of the archives that contain them.

The potentials of modalities for the preservation and use of information

through communication depend greatly on technological innovation.

We are currently defining tools and methodologies for the reorganization

of the existing material to favor more-dynamic, more-creative,

and more-interactive participation by members of and by visitors

to the virtual community. Users select, from the reply of the

multiarchive, the data of interest for their work, creating a

new object summarizing these, which can in turn be cataloged and

stored in a new archive.

A Path toward the New Technologies

Another objective of the Corpus is to provide an updated laboratory

in which new technological tools supporting social and cultural

needs can be proposed and experimented on as they appear on the

scene. Consequently, the infrastructure of the virtual community

must keep pace with the trend of technological progress in order

to understand the usefulness and applicative, or methodological,

innovation of the instruments proposed and to see whether they

can be adapted and reused in different environments, or whether

further developments can be proposed.

Today the technological challenge to the Corpus, which is currently

in a prototype version, is the creation of tools for growth of

the Corpus through the personalization of information and its

reprocessing according to the new technological standards of the

World Wide Web. These are matters purely of infrastructure (such

as the protocols for communicating and transferring data on the

Net), as well as difficulties in the presentation of documents

(which changes with the type, or even the version, of browser

employed, and which does not, in any case, meet current graphic

demands), and of the problem of the explicit rendering of the

significance of a document to improve information retrieval.

The approach taken to solve these problems considers (1) the use

of new languages that integrate or, in the end, replace HTML and

(2) the possibility of assigning the client or the browser a greater

role in the processing (depriving the latter of its autonomy—that

is, facilitating the interpretation of different syntaxes of the

HTML through tools that allow extension of the language itself).

The recently proposed metalanguage, XML (extensible markup language)

[Bray et al., 1998] permits the definition of new syntactical

elements, specifying separately the content, structure, and style

of representation. XML is a language for a structured approach

to the description of documents—that is, specifying the component

parts with their relative attributes. A DTD (document-type definition)

is composed in which the syntax and the semantics of the tags

are defined. XML extended with DTD is used for describing an instance

of a document and organizing the contents. The DTD provides a

grammar that can automatically verify whether a document derived

from it is a valid XML document. Representation of the various

elements can be left to the author of the document, who can define

this information either within the DTD or in attachments written

in languages devised for that purpose, one of which is the emerging

XSL (etensible stylesheet language). XSL allows the browser to

personalize the visual presentation of the XML document without

any interaction with the server. The potential of XML associated

with XSL lies in the fact that, by the application different stylesheets,

the same XML document can be used by different users, who adapt

its presentation to their own needs, and to the interface, or

applications, used. The fact that a document can be formally and

automatically analyzed—focusing separately on its structure and

presentation—makes it possible to identify any recurring components

of the document and to determine their importance on the basis

of their position in the textual hierarchy. We can expect XML

to become the basic tool for the exchange of data on the Internet.

XML is a meta-language that defines new languages, including new

metalanguages. A good part of the scientific community considers

XML a panacea for the various problems regarding the WWW. For

example, the XOL language (XML-based ontology exchange language)

[Karp et al., 1999] allows the formal definition of the set of

concepts, relationships, objects, and constraints characteristic

of a domain of interest—such as African culture in Italy. The

definition of an ontology can be expresssed in XOL, and this definition

used as a tool for mediating among different formats and uniforming

them. A specific case is that of uniforming the schemata—or instances

of documents—managed by RDBMS, OODBMS, or IRS, all belonging to

the same thematic domain. Consequently, in the case of Africa,

XOL is a valid candidate for expressing the CDM.

Ways of breaking down into fragments and storing XML documents

in specialized databases and, vice versa, tools for translating

the structure and contents of the databases in XML documents are

currently being defined. XML documents are roughly classified

as datacentric documents for further processing, characterized

by a fairly regular structure, fine-grained data, and documentcentric

documents meant for direct, human communication and characterized

by an irregular structure and larger-grained data [Bourret, 1999;

Widom, 1999].

XML documents are transferred to and from a database by mapping

the document structure to the database structure and, vice versa,

using a template- or model-driven approach. In the former, commands

are embedded in a template that is processed by data transfer

programs. In the latter, an ontology expressed in an appropriate

language (XOL) is used as an intermediate in order to map the

structure of the XML document to the structures in the database

and vice versa.

Relational databases, while suitable for storing datacentric documents,

do not constitute the optimal solution for storing documentcentric

documents, because such databases cannot efficiently provide for

order, hierarchy, irregular structure, and fields of variable

length. They can, with certain limitations and leaving much of

the work to the user, be used to store XML documents, as described

by Mark Birbeck on the XML-L mailing list: a DTD can be translated

with a five-table system. In this scenario it is inevitable that

we must face the new technological challenge of defining a new

infrastructure for the Corpus, in its function as multiarchives

and support for documents customization, using the XML as a metalanguage

to standardize the proposed CDM structure. Consequently, we are

taking two steps:

- Designing and producing tools in Java that allow the dynamic construction

of a reference ontology for the material present in the Corpus

Africanisticum, so that it can be constantly updated by including

new archives or new documents with only a minimum effort on the

part of the user

- Modeling the schemata of the local archives by using a DTD compatible

with the ontology created. Exploiting developments in the XOL

language, with which every possible ontology can be easily converted

into a DTD

These activities will produce the skeleton of the new infrastructure

of the Corpus Africanisticum virtual community, for which we are

designing support tools for:

- An interface in Java that can identify, once the set of archives

to query has been chosen, the DTD of the corresponding domain

- Translation of the user's specifications into the syntax of the

various archives

- Assignment to each archive of a component DTD and the principal

DTD, so that the results will be given in an XML document with

a structure that depends on the domain but that is homogeneous

in its various elements

- Presentation of the result of a query in the form of a structured

document that can be recataloged and included in a new database

or, even better, the organization of which can be exploited to

create paths for personalized navigation

In this way, XML can also be used as a language to define the

user-system interface for interaction, querying, and visualization.

Animating the Virtual Community of Navigators

The fruition of the community is supported by tools that manage

the services for interaction and interactivities and, together

with the consultation for navigation, allow an exchange of comments,

notes, and messages from the same working environment and through

the same channel.

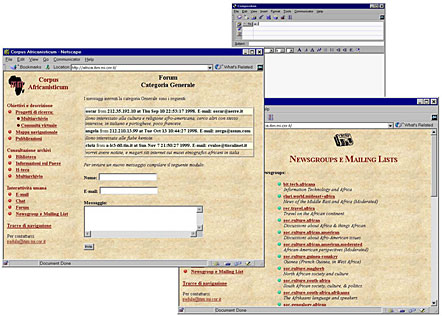

The Corpus offers instruments/services for communication and participation

within this neocommunity (figure 4), subsidiary of the real one,

through a CMC (computer-mediated communication) in either synchronous

mode (communication between two or more interlocutors, as in a

normal telephone call or face-to-face) or asynchronous mode. Members

of the Corpus Africanisticum virtual community can communicate

with each other on the Net through services such as e-mail, news

groups, forums, and chat lines.

Figure 4. CMC services offered by the virtual community

With e-mail they can send messages in asynchronous mode to other

people or programs. Messages received in the electronic mailbox

can be read at a later time.

A News group is a permanent electronic conference in which people

with a particular interest in common participate. Messages sent

to a news group, unlike e-mail, are not addressed to a single

individual but get posted for a certain length of time on a virtual

bulletin board where anyone who wants to can read and comment

on them. It is a tool for asynchronous, collective, and even moderating

participation.

The Corpus also has a forum service, with three discussion groups:

the General Forum, the Guestbook, and the Calendar of Events.

The chat line is a conversation in real time and allows for interactive,

synchronous exchange of messages. One person writes a message

and receives the answer by his interlocutor immediately on his

screen. Usually, no control is exercised over who particpates

or the subject discussed. Nor does any trace remain of the messages

exchanged in a chatting session. The chat line of the Corpus Africanisticum—to

restrict communications to the theme of the Corpus— has been designed

in an asynchronous mode, although the user does not perceive it

as such. The service is accessed by registering one's name (nickname),

e-mail address, and password. These data are sent to the Web administrator.

Once registered, the user may begin to communicate with the other

participants on the list of persons connected at that moment:

he selects the person he wants to chat with by sending a message

through the form shown on the page. Both the messages he sends

to other members of the virtual community and those sent by other

members to his attention can be viewed on the screen.

Conclusions

Digital society gives added value to preservation by allowing

fruition of the object (hypermedia document), making it possible

to operate on a shared base of documents and adding one's own

contributions to extend the boundaries of the documents, using

the services for interaction to add creative, dynamic, and transitory

surroundings. The virtual community is responsible for the evolution

of the document, which now resembles a channel of communication

rather than the subject of a conversation, more similar to our

idea of communication than to that of artifact. It becomes the

concrete expression of a semantic emergence, without a predefined

description of its contents; its uniqueness vanishes, and its

contours are not precisely indicated, except by the URL, the addresses

of the Net, and its heterogeneous components; and there is no

longer a predefined beginning and end to the reading. As a consequence

of its transitoriness, what counts in a document are management

in time of its successive versions, management of the references

to its dynamic components, and access to important information.

The materiality of the object becomes an aspect: the object can

be seen in a situation of complete artificiality. Virtual communities

of things allow the artificial world built by man—such as libraries

and museums, that is, human archives—to be even more artificial,

because the material relationship with the object, which is simulated

in the digital mode, has no relevance. Physical man in his research

in the virtual world can more fully exploit the resources of knowledge

because he can do so with little effort, much more rapidly, and

without moving from his workstation.

The virtual community provides a collaboratory [CTT, 1997]—that

is, a virtual—workplace for a technological development that originates

and is modulated by social needs.

References

Bourret Ronald. XML and Databases, December 3, 1999, http://www.informatik.

tu-darmstadt.de/DVS1/staff/bourret/xml/XMLAndDatabases.htm.

Bray, Tim, Jean Paoli, C. M. Sperberg-McQueen. eXtensible Markup

Language (XML) 1.0, February. 1998, http://www.w3.org/TR/1998/REC-xml-19980210.html

CTT (Canada’s Technology Triangle). The CTT Community Intranet—Working

Paper, July to October 1997.

De Kerckhove, Derrick. The Skin of Culture. Toronto, Canada: Sommerville

House Books, 1995.

Jensen, Mike. “Internet Connectivity for Africa”, OnTheInternet,

September-October 1997, pp. 32-37.

Jensen, Mike. An Overview of Internet Connectivity in Africa,

September 1998, http://demiurge.wn.apc.org:80/africa/afstat.htm

Karp, Peter D., Vinay K Chaudhri,. and Jerome Thomere. XOL: An

XML-Based Ontology Exchange Language, July 3, 1999, http://www.oasis-open.org/cover/xol-03.html.

Pierre Lévy. L’intelligence collective. Pour une anthropologie

du cyberespace. Paris: Éditions La Découverte, 1994.

Pierre Lévy. Qu’est-ce que le virtuel? Paris: Éditions La Découverte,

1995.

Pierre Lévy. Cyberculture. Rapport au Conseil de l’Europe, Paris:

Éditions Odile Jacob, 1997.

Mozzatti, Marco, and Marco Padula. Corpus Africanisticum: archivi

multimediali sull’Africa esistenti in Italia, Rapp. Int. ITIM-CNR,

Marzo 1996.

Padula, Marco, and Davide Musella. Seeking Emergences from Digital

Documents in Large Repositories, Sémiotiques, n. June 12, 1997,

pp. 12 – 150.

Padula, Marco, Amanda Reggiori, Elena Gallo, and Cristina Ghiselli.

Conservazione e divulgazione nella società digitale, Archivio

Fotografico Toscano, October 1998.

Pitoura, Evaggelia, Omran Bukhres, and Ahmed Elmagarmid.Object

Orientation in Multidatabase Systems, ACM Computing Surveys, 27

(2), June 1995.

Reggiori, Amanda. Internet come strumento di partecipazione democratica:

il caso delle reti civiche, thesis, Specialization School for

Mass Media Communications, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore

of Milan, Istituto di Scienze della Comunicazione e Spettacolo,

February 1996.

Schuler, Doug. Community Networks: Building a New Participatory

Medium, Communications of the ACM, 37 (1), January 1994, pp. 39-51.

Schuler, Doug. Computer Support for Community Work. Designing

and Building Systems for the “Real World.” CSCW 98 Tutorial, November

15, 1998, Seattle, Washington, http://www.scn.org/ip/commnet/cscw-tutorial-1998.html.

Widom, Jennifer, Data Management for XML, June 17, 1999, http://www-db.stanford.edu/~widom/xml-whitepaper.html.

|

|